A current issue in UK politics is the tax status that should be accorded to the married. This is hardly a fit subject for polite company, but it means that there is a sudden interest in who gets married and who does not, and renewed discussion about whether the institution of marriage confers a benefit on its adherents, or whether it simply attracts a better sort of person in the first place. The evidence seems to favour the latter explanation, or so it would seem from a study conducted by Goodman and Greaves entitled “Cohabitation, marriage and child outcomes” produced by the Institute of Fiscal Studies, April 2010. http://www.ifs.org.uk/comms/comm114.pdf

You may wonder what fiscal studies have to do with the institution of marriage, and whether this topic is best left to religious leaders, but governments with a penchant for taxing their long-suffering citizenry stick their fingers into the most intimate regions, transforming even the most private matters into a mesh of brigandage. There are taxes and tax benefits to marriage, to not being married, to being tenants in common, to leaving money to a spouse, to dying married, to being divorced, to having children, to not having children, and sundry other matters. You should take tax advice before so much as smiling at a stranger.

The authors have done a thorough piece of work on a familiar sample, the

Millennium Cohort Study which has graced these pages before. It is a longitudinal data set which initially sampled almost 19,000 new births across the UK between 2000 and 2002. The sample design disproportionately selected families living in areas of child poverty, in the smaller countries of the UK and in areas with high ethnic minority populations in England. As we learned before, it was a reasonably good sample until everyone started moving about, as humans usually do, and as the poorer respondents disproportionately dropped out of the study. Tag them all at birth, make them report back forever on Twitter, and autopsy them all at death. Meanwhile, back to the study.

The authors decided to restrict their sample to those children born to couples (30% cohabiting, 70% married). It turned out that there is not much difference between the two, so one is left wondering if including single parenthood would have had an effect. A pity we won’t know this. As the authors are aware, modern relationships follow a pattern: out of roughly 10 sexual partners the last one is chosen for cohabitation; then if things go well the couple have a child and marry sometime afterwards; though some marry a little before; and then after a while if things don’t work out some couples separate and repeat the process, almost always sequentially, occasionally in parallel.

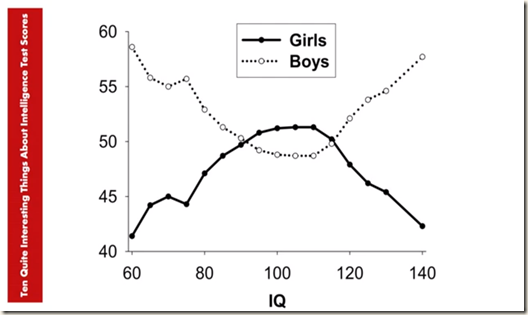

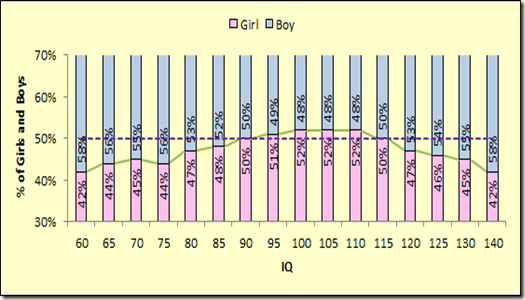

A good point is that we have some IQ data on the verbal part of the British Ability Scale, and though at 3 year and 5 years of age we can get some good indications of ability, we lack the power obtained at age 11. There is also child development data based on parental report. As I have already revealed, there is not much evidence that marriage improves child outcomes at age 5.

“We have shown that parents who are married differ from those who are cohabiting in very substantial ways, particularly relating to their ethnicity, education and socio-economic status, and their history of relationship stability and the quality of their relationship even when the child is at a very young age. Once we take these factors into account, there are no longer any statistically significant differences in these child outcomes between children of married and cohabiting parents.”

“much of the gap in educational and social and emotional outcomes between the children of cohabiting and married parents appears to be due to differential selection into marriage compared with cohabitation, largely on the basis of parental education and socio-economic status. These characteristics of the parents explain differences in cognitive development almost entirely, while some differences in social and emotional development remain. Much of the remaining difference in social and emotional outcomes is accounted for by differences in relationship quality between parents who are married and cohabiting when their child is born.”

The overall result of no difference (rather than the detailed findings) has been seized upon as a reason not to favour married couples with a tax break. Frankly, the tax system is so complicated that I doubt this change will make much of a difference, other than to complicate things further.

Here are the key findings drawn directly from their paper:

Just over half of mothers who are Black Caribbean are married when the child is born, compared with about 70% of mothers who are White. By contrast, almost all mothers who are Bangladeshi, Pakistani or Indian are married when their child is born.

Mothers of all religious faiths are significantly more likely to be married rather than cohabiting compared with mothers of no religion.

Both mothers and fathers in married couples are over twice as likely to have a degree as their counterparts in cohabiting couples. Married mothers are also slightly less likely to have problems reading in day-to-day life.

Fathers within married couples are twice as likely to have a professional occupation as cohabiting fathers.

Couples that are married at the time of their child’s birth are around twice as likely to be in the highest household income quintile. Married couples are much more likely to own or have a mortgage for their home.

18% of mothers in cohabiting couples first gave birth before they were 20, compared with 4.2% of married mothers, while over 30% of married mothers were over 30 at the time of their first child’s birth, compared with 21% of cohabiting mothers.

Married couples are much more likely to have lived together for a longer period of time prior to their child’s birth than cohabiting couples: over half of married couples have lived together for more than 6 years, compared with 16% of cohabiting couples. Almost 40% of cohabiting couples had lived together for less than 2 years, compared with only 8% of married couples.

Mothers in married couples are much more likely to report that their pregnancy was planned; this was the case for 75% of married mothers compared with 47% of cohabiting mothers.

There is some difference in ‘early’ relationship quality between married and cohabiting couples. For example when the child is 9 months old, 31% of married mothers report that their partner is usually sensitive and aware of their needs, compared with 24% of cohabiting mothers.

Cohabiting couples are considerably more likely to experience a period of separation of a month or longer before their child is 3 years old; this is the case for 26% of cohabiting couples and only 7% of married couples. Couples that are cohabiting at the time of their child’s birth, rather than being married, are also less likely to live together when their child is aged 3.

Mothers who are married at the time of their child’s birth and their child have slightly better health outcomes than mothers who are cohabiting. The child is slightly less likely to have a low birthweight (5.8% of children born to married couples, compared with 7.4% born to cohabiting couples) and slightly less likely to have been born prematurely (7.7% compared with 8.5%).

Mothers in cohabiting couples when their child is born are much more likely to smoke when the child is 9 months old: 41% of mothers in cohabiting couples smoke, compared with 15% of mothers in married couples. Mothers in cohabiting couples are also less likely to breastfeed their child at all, and slightly more likely to have a high score on an index of ‘mother’s malaise’ when the child is 9 months old, which is indicative of depression.

Fathers in married couples are slightly more likely to have the lowest level of involvement with their child at 9 months old, but cohabiting fathers are less likely to rate themselves as ‘good’ or ‘very good’ parents when their child is aged 3: 57% of fathers in married couples have this belief, compared with 44% of fathers in cohabiting couples. There is less difference in the percentage of mothers in each household type who believe they are ‘good’ or ‘very good’ parents.

Couples that are married at the time of the birth are more likely to have a more regular routine for their child: 46% have a regular bedtime for the child at age 3, compared with 39% of cohabiting couples. Married couples are also more likely to provide a better home learning environment at age 3 – for example, 67% read to their child daily, compared with 58% of cohabiting couples.

What are the outcomes of children born into married and cohabiting families?

By the time children are aged 3, there are already statistically significant differences in child outcomes between children born to married parents and those born to cohabiting parents. On average, children born to married parents display better social and emotional development and stronger cognitive development than children born to cohabiting parents.

The differences in children’s social and emotional development are much larger than the differences in their cognitive development at both age 3 and age 5.

The most negative outcomes for children are, on average, amongst those whose biological parents have split up, regardless of the formal marital status of the parents before they split.

The differences we observe between children born to cohabiting parents and those born to married parents are relatively small in comparison with other attainment gaps, such as the gap between children born to parents with a high and low level of education, between children born to lone parents compared with parents in any form of couple, or between parents with high and low income.

The gap in cognitive development at ages 3 and 5 between children born to cohabiting parents and those born to married parents is greatly reduced and is no longer statistically significantly negative after differences in parents’ education, occupation, income and housing tenure are controlled for. This suggests that the lower cognitive development of children born to cohabiting parents compared with children born to married parents is largely accounted for by their parents’ lower education and income, and not by their parents not being married.

The gap in social and emotional development at ages 3 and 5 between children born to cohabiting parents and those born to married parents is reduced by more than half, but remains statistically significant, once differences in parental education and socio-economic status are controlled for. This suggests that the majority of the gap in social and emotional development of children born to cohabiting parents compared with children born to married parents is largely accounted for by their parents’ lower education and income, and not by their parents not being married.

We have shown that the children of married parents do better than the children of cohabiting parents in a number of dimensions, particularly on measures of social and emotional development. But we have also shown that parents who are married differ from those who are cohabiting in very substantial ways, particularly relating to their ethnicity, education and socio-economic status, and their history of relationship stability and the quality of their relationship even when the child is at a very young age. Once we take these factors into account, there are no longer any statistically significant differences in these child outcomes between children of married and cohabiting parents.

Comment

This is a good study, carefully done and reported. It vividly illustrates the interpretive problems we encounter in research when we “control” for variables which relate to behavioural choices. For example, anyone who still smokes, and smokes while raising a child, does so in the knowledge that they are affecting their health and that of their offspring. We can control for this in the statistical sense, by calculating what their health would be like if they did not smoke, but in real life we cannot control for their behaviour (other than giving them warnings, taxing cigarettes and so on). Life involves choices, and the effects of choices accumulate along the lifespan.

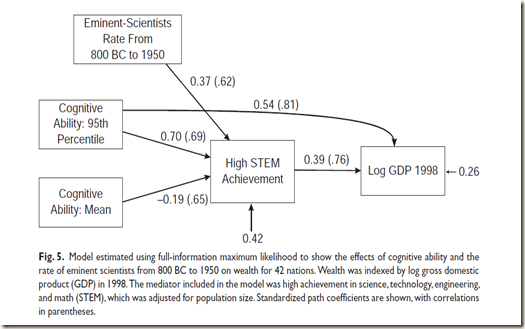

The study could have been improved by using Structured Equation Modelling, though I still welcome old fashioned regression results, despite their complexity. As is usual in contemporary social science, there is no mention of possible genetic transmission of ability. All the significant difference which impact on child development are firmly described as being due to education and status (in theory, goods which could be distributed to people, rather than emblems of attainment).

In summary, you could argue that the conclusions should be: Forget about formal marriage, and concentrate on who you shack up with: someone who is bright (measured here by scholastic attainment and professional occupation) diligent and future oriented (measured here by socio-economic status and owing property) of good character (measured here by spouse sensitivity) dependable (measured here by not dumping you within 3 years) and someone who appears to be in good health and does not blow cigarette smoke in your face. You must not mention it, for fear of being unfashionable, but you are searching for someone who comes from a good family, and must even avoid those who were abandoned by their own parents and taken into care. In times gone by this was referred to as good breeding. Now it would be called “good genes”.

It is interesting that, in seeking to attack the tax and marriage political proposal, some commentators have overlooked the actual results of the paper, which point clearly to the advantages of living a considered life, based on thought and behavioural restraint. These are high ideals, but many people manage to attain them, most of the time at least.

Although this paper is associated with the Institute of Education, it may in time achieve the status of a revolutionary tract. On reflection, a counter-revolutionary tract.